WHAT is the adventure film festival:-

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their bliss.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their work.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their videos.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their expertise.

The Adventure Film Festival is a global online adventure film competition.

IF you have an adventure film worthy of global recognition = submit it.

IF you are an adventure film maker = build your story / build your brand; it is our job to help you build your business.

Adventure Film makers / our stars – we want to help you develop our global industry…

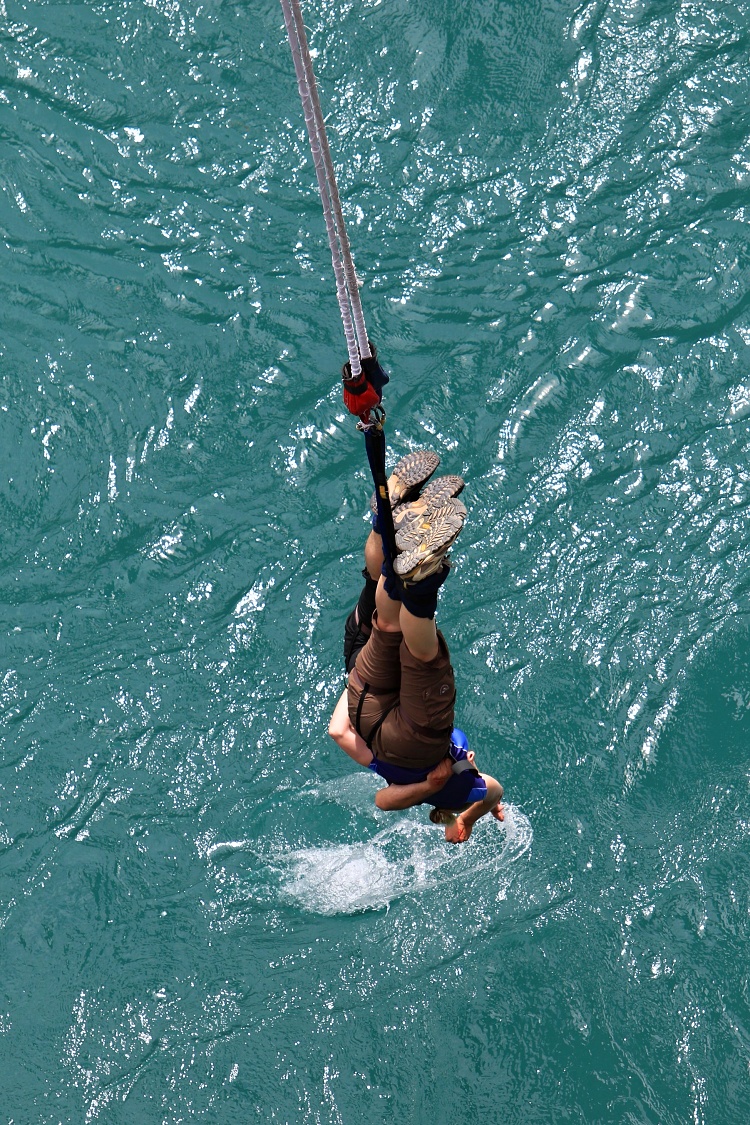

FIRST-TIME BUNGEE JUMPING – WHAT IT’S REALLY LIKE (KAT’S STORY)

We love adventures.

We have done rock climbing, zip-lining, diving, swimming in a cage with sharks, white water rafting, skydiving and extreme roller coasters.

You name it, and either we have done it, or it is on our bucket list.

Bungee jumping had been on our list for a long time.

But in the end, it proved much harder than it seemed in photos and videos.

Bungee jumping took our adventures to another level, and we learnt a few life lessons.

While we were on our last road trip in New Zealand, we knew this was the best place to try it.

New Zealand is the birthplace of bungee jumping, which has been popularised here.

The country is also renowned for innovation, excellent facilities, many years of experience and, most importantly, an excellent safety record.

Queenstown is called the ‘Adventure Capital of the World’, so we felt that we should do our first jump there.

This post has been written from Kat’s point of view because this has been a rather personal and intense experience.

Petr’s self-preservation instinct is quite relaxed compared with most people, so his experience made for another story. You can read it here.

BUNGY OR BUNGEE?

Both words have the same meaning.

Bungy is the spelling used mainly in New Zealand, while bungee is more common in the rest of the world.

SKYJUMP LAS VEGAS

The list of adventures I have been through is long, and I’m proud of that.

There is only one exception, SkyJump Las Vegas, the world’s highest controlled descent.

The launching pad is located on the 108th floor of the Strat Hotel, Casino and SkyPod (formerly Stratosphere Casino, Hotel & Tower), 260 metres (855 feet) above the Las Vegas Strip.

While in Las Vegas, we decided to do the night jump. What could go wrong, right?

I was confident because we had just done our first skydiving in Cuba a few months before, and I loved it.

We had jumped out of an old aeroplane 3 km (1.9 miles) above the ground, so it couldn’t be worse, right?

I was wrong. It was.

I was fine until I got to the jumping platform, where everything changed.

When I started to feel the wind on my face, I realised what height I was at.

I was supposed to jump into the dark but could not do it. My confidence was gone.

I chickened out.

What was so different between skydiving and this jump?

I was on my own. There was no experienced instructor I could hang on to.

I took the challenge too lightly.

On the other hand, Petr managed to jump. The fee we had paid was non-refundable, so he jumped twice not to waste the cost of my ticket. How cool is that?!

KAWARAU BRIDGE BUNGY, QUEENSTOWN

When we arrived at Queenstown in New Zealand, I knew that if I didn’t do it here, I would probably never do it.

But after I failed in Las Vegas, I was afraid I would give up again.

At first, we visited the Kawarau Bridge Bungy to see what it was like.

It’s the world’s first commercial bungee, with a height of 43 metres (141 feet).

The location was beautiful – a wooden bridge in the Kawarau gorge overlooking the river with its turquoise water.

But the scenery was the last thing on my mind!

People were queuing for the jump. There were many of them – men, women, young, middle-aged…

They all seemed to be just ‘normal’ people, no adrenaline junkies.

I thought that I could do it too if they could do it.

I had done so many potentially dangerous activities before and didn’t want to look like a coward now.

The faces of people who were just about to jump said it all.

They were afraid, really afraid.

I realised that everyone felt fear (except for those adrenaline junkies).

And that’s what it was all about – overcoming the fear and doing it despite it.

So, we decided to jump the following day.

Unfortunately, we mentioned this to the Airbnb host we stayed with that night.

Instead of a few words of encouragement that we needed, she said that bungee jumping was the worst experience of her life.

After standing on the jumping platform for ages, she only jumped (with closed eyes) because her friend threatened to push her.

It didn’t help at all. It wasn’t something I needed to hear.

As you can imagine, I didn’t get much sleep that night.

I went from “Yes, I can do it, I have done worse things.” to “What is the point of doing it if I won’t enjoy it? Let’s leave it till another time. ”

In the morning, I still didn’t know if I was going to do it or not.

We arrived at the Kawarau Bridge and watched people jumping for a while.

Petr asked if I was in so that he could buy the tickets.

I still didn’t know what to do. I hated to admit that I was so scared.

We agreed that Petr would jump first, and then I would decide if I wanted to do it or not then. He managed a beautiful dive; it looked so easy. He told me it wasn’t too bad and I should do it too.

I still didn’t know what to do.

Then, we saw a couple preparing for a tandem jump (the girl was so scared that she didn’t do it in the end).

I thought it would be easier to jump together with Petr because I could hold him.

If anything went wrong, he would know what to do (he always does!).

I knew if I didn’t do it here and now, I would never do it because I would find another excuse.

A tandem jump was available, and we bought the tickets.

We got weighted, signed a waiver and put on our harnesses.

We were told which way to jump and hold each other for a smooth experience.

The preparations took longer because they had to calculate the correct length of the ropes for two people jumping together, which wasn’t that common.

Each of us was tied to a separate rope, and we held each other behind our backs.

Petr got ready first because he was taller.

Then, it was my turn.

The staff were excellent; they made fun and talked to us all the time to make us feel more relaxed.

I had a smile on my face, but when I got to the jumping platform, I felt paralysed by fear.

I could barely move.

But I didn’t question the safety of the ropes.

It was the feeling of having to jump into space from such a height.

I was trying not to look down and was looking at the surroundings.

I was forcing myself to think about something else, but it was hard.

And there we were – standing on the jumping platform, tied to each other, smiling for the cameras but freaking out inside (at least I was!).

It felt like being in a movie – and then the guy said: “You are ready to go – three, two, one, JUMP!”

And we jumped.

I let go and DID IT.

I managed to jump at the exact second as Petr.

It was a special moment that we shared.

It was just a split second until gravity grabbed us, and we started falling.

Then I didn’t remember anything until we reached the water.

I don’t know if I passed out or if it just happened so quickly that my brain couldn’t process it.

But I was probably fully conscious because Petr told me later that I was screaming the ‘F’ word all the way down!

We were thrown up and down like two puppets when we got down to the river, and the ropes stretched.

The fear was gone, and we were laughing and enjoying the moment.

After we stopped moving, a boat came underneath us and picked us up.

I was shaking but so happy that I had made it.

But deep inside, I knew I needed to do it alone.

I was a step closer to that now.

Petr hadn’t had enough and wanted to conquer the nearby Nevis Bungy too, because we were leaving Queenstown the following day.

It’s New Zealand’s highest bungee (134 metres, 440 feet). People jump from a cable car cabin hanging between two mountains.

I wasn’t ready to do that because I was still processing our tandem jump. Just standing in the unsteady cabin was scary.

Fair play to Petr that he managed to jump as effortlessly as only he can.

AUCKLAND BRIDGE BUNGY

Two weeks later, we arrived in Auckland.

I knew it was my last chance to jump on my own because we were leaving New Zealand soon.

The Auckland Bridge Bungy was perfect because the jump was above the sea, so I convinced myself that nothing could happen.

If anything went wrong, I would end up in the water, right?

We booked our tickets online and got picked up by the minibus.

We put all the gear on, got a quick safety briefing and off we went.

We had to walk to the middle of the Auckland Bridge to get to the jump pod.

At the moment, the bridge is not accessible to pedestrians.

The only way to get stunning views of Auckland’s skyline is the Bridge Bungy or Walk.

The walk to the pod felt never-ending.

I was trying to distract myself by looking around and thinking about anything else but the jump.

Petr was the most experienced jumper in the group, so he went first.

He decided to jump backwards – how crazy is that?!

He requested the ropes to be adjusted to get as deep into the water as possible.

He dived up to his knees.

When he came back up, he was laughing as if it was all just a piece of cake.

Two more people were jumping after him.

I could see that they were scared, but they made it.

Then, it was my turn.

Again, the staff were terrific.

They were making jokes, but nothing could help me at that stage.

I was trying to keep calm, but I was so frightened that I could barely move.

I felt like a robot, just doing whatever I was told.

But I had decided to do it no matter what, so I kept going.

The guys got my rope and gear set so I could touch the water as I requested.

They helped me to get to the jumping platform.

That was it.

Now or never.

I was standing on the platform, trying not to think about what I would do and admiring the bridge’s impressive construction to distract my mind.

I was freaking out.

A few smiles for the camera, and then they said: “Three, two, one, JUMP!”

And I JUMPED!

I just leaned forward, and gravity did the work for me.

The horror of the last few seconds before the jump suddenly changed into pure joy when I started falling.

I was enjoying the moment and smiling until I hit the water.

It didn’t hurt at all, and I got into it smoothly.

I dived up to my waist, which I didn’t expect.

I had my mouth open and tasted the salty water.

In the end, this was the best part of the experience.

I couldn’t believe that it was over and I MADE IT! I came back up shaking but happy.

This time I enjoyed the views on the way back to the mainland.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Bunge jumping was the hardest thing I have ever done (so far).

I had never felt so much fear before.

But at that moment, when I was jumping on my own, I realised one crucial thing that has profoundly affected my life.

I realised that I could really do ANYTHING I wanted.

It might be scary, hard or seem impossible.

But if I really want it, I can find the way by taking small steps forward.

And if I can do it, you can do it too (whatever it is).

PS: When we return to Las Vegas one day, I will jump off the Stratosphere Tower…. I know I can do it now…

For more information and details : https://travelfromsquareone.com/first-time-bungee-jumping/

From summit to sea: a snowboarding adventure in the Arctic Circle

There are no lifts in Norway’s picturesque Lyngen Alps, so if you want to ride down a mountain to the shore you have to hike up it first

I’m on top of the world, in all senses of the term: we’re 500 miles inside the Arctic Circle in Norway’s Lyngen Alps and I’m buzzing at having reached the summit of Riššavárri, after a 31/2-hour hike.

Jagged white peaks rise starkly from snaking, deep blue fjords, the sun is shining, the light’s amazing – and there’s no one here but me and my guide, Mikal Nerberg. With more than 60 summits over 1,000 metres, the Lyngen Alps have a quasi-mythical status among hardcore skiers. It’s a purely touring destination: there are no ski lifts, so any mountain you want to ride down you have to hike up, using “skins” on your skis for grip. With ski fans increasingly wanting a fitness break, rather than just boozy lunches and downhill meanders, touring is a growth area.

The Lyngen Alps is where alpine guides come on holiday once their European season finishes, and where they bring their best and favourite guests. I’m here in early April but the season runs until June, when there’s skiing in the midnight sun.

Instead of getting a resort bus or cable car to our starting point, we take a ferry across the fjord from Lyngseidet to Olderdalen. Our hike begins at sea level, rising up through a forest of elder and silver birch, the trees bowed under the weight of the snow. Mikal is on touring skis, while I’m on a splitboard – a snowboard that splits in two so it can be used like touring skis. The way isn’t too steep, but Mikal insists on a slow pace and makes us stop for snacks every hour to keep energy levels up.

Coming out of the woods we see our target summit, high in the sky, and still another 1,000 metres away. The climb quickly gets steeper but at the hour-two stop I still feel OK. As we reach hour three, however, I begin to wonder if I’ll ever make it to the top.

I put my board together, while Mikal checks the snow to see which line would be our best descent. We set off, navigate some juddering wind-ruined snow then find a pocket of lovely soft pillow-like powder. Further down we ride super-fast spring slush, passing giant boulders of icy snow, and then cut into the forest we climbed through earlier, dodging the tightly packed tree trunks and stumps as if in a computer game. We emerge into a snowfield and ride down to the fjord, a complete run from summit to sea.

Most skiers and snowboarders stay at the Magic Mountain Lodge (bunks from £40pp full-board) in Lyngseidet – the main, albeit tiny town – but it’s fully booked, so I stay in a private rental house in a hamlet 12 miles north (Take Me Away, Holiday House, from £110 a night, sleeps four). Like almost every house in Lyngen it looks straight out of the Cabin Porn book: white wood with a pretty green trim and a 1960s-style kitsch interior. On my first night a white hare dances in the drive.

On day two we drive north to the waterside hamlet of Koppangen, where the road stops abruptly and turns into mountain. From here we set off for the 950-metre summit of Goalborri. Yesterday’s blue skies have switched to snowy showers. Before long it’s too steep and slippery to proceed by splitboard so I strap it to my backpack, put crampons over my boots, and Mikal hands me an ice axe for stability.

This feels more aerobically tough than the day before – like climbing a snowy ladder, with the odd rock to scramble over – but we cover a lot more ground. After 21/2 hours we reach the top. Tiredness only hits as we start to ride the steep but reassuringly wide couloir. Lower down, we put down fresh tracks in soft spring snow, before popping out at the fjord.

Later that night I see the wisps of the northern lights rise in the sky. It’s beautiful but doesn’t come close to being the highlight of my trip, nor does the snowboarding down, fun as that was. The bit I love best has been the hiking up, the hard work of earning those runs down in this wild, silent and most un-ski resort-like place. Which also happens to be as easily reachable from the UK as the European Alps.

We Turned an Abandoned Church Into a Skatepark. Then Tragedy Struck.

I found out that our place of worship was burning around 2 a.m. I woke up to seven missed calls and over 50 messages. If the texts hadn’t come with pictures of the bell tower engulfed in flames, I wouldn’t have believed them. Everyone is safe, but it’s destroyed. The fire is still going. Church is gone. For years the place had been our sanctuary, and now it was ash.

Back when we were still St. Louis kids and before we had kids of our own, my friends talked about turning the long-abandoned Catholic church into a skate park. We grew up together in a pack of feral teenagers who skated up and down Delmar Boulevard, the east-west artery that cuts through the city. We loitered outside the Shell station and Racanelli’s Pizza and Vintage Vinyl. We sat in piles of wrists and legs and hormones to claim our space on the concrete. They called us the Loop Rats, just a bunch of dirty pests the store owners had to shoo away from their doors.

Like a lot of young people who grow up in uncool places, I thought I had to get to a shiny metropolis to build success. For over a decade, I chased achievement elsewhere: New York City, Los Angeles, Boston. But it was in returning home that I became a part of building something increasingly rare and meaningful: a community.

A few years ago, my friends and I pooled our resources to turn St. Liborius Church, a nationally registered historical site and the largest Gothic revival church west of the Mississippi, into a community space. Trying to develop a skate park inside a massive church was never a part of my five-, 10- or any-year plan. But I fell in love with the idea of giving a new generation of St. Louis kids a spectacular place where they would be welcome and where no one would ever shoo them away.

Transforming St. Liborius into Sk8 Liborius was a D.I.Y. effort. The good part about living in an undesirable place is the same as the bad part: No one cares what’s happening here. This is mostly hard, like when jobs dry up and infrastructure crumbles. But it also means that unlike in America’s aspirational cities, where creativity is reserved for the rich and their children, large-scale creative projects are still accessible to the non-generationally wealthy. No one is coming to repair America’s forgotten cities except for the people who live in them. In St. Louis alone, there are about 25,000 abandoned buildings. The überrich would rather visit Mars than save St. Louis.

So for years, we hauled shovelfuls of dead pigeon carcasses out of the corners of the church to clear space for construction. We called ourselves the Dead Pigeon Club, and some people even got tattoos of them, still punk even when pushing 40. I almost had a panic attack when one very alive pigeon flew uncomfortably close to my face in the bell tower. Hundreds of local volunteers lent their skills to this project. They ran the gamut from tradespeople who spent their Sundays tuckpointing, welding and laying concrete to office workers who researched 501(c) funding and historical building grants and talked to lawyers.

Although the process of building Sk8 Liborius took over a decade, our community found national attention only this summer.Predictably, it was because something tragic happened.

Before the four-alarm fire, Sk8 Liborius was a beautiful place in a place not known for beauty. Some of the church’s original stained glass was still intact. Cobalt blue, canary yellow and rose hues depicted the stories of the New Testament. A partly shattered portrait of Mother Mary, a tree branch peeking through her left eye. If you bit it on a ramp, as you lay on your back, the gold mosaic ceiling tiles comforted you with their sacred geometry.

The walls were adorned with murals by local artists. The only rule was: No covering up the original religious artwork, so lunettes more than 100 years old floated above graffiti tags like “STL Punk.” It was impossible not to feel the Holy Spirit when you were walking through the cross-shaped open space that led to the altar, where dozens of broken skateboards lay in sacrifice.

Skateboarding is naturally a socially inclusive sport, and the “congregation” that formed was welcoming to all. Teenagers from impoverished parts of North St. Louis skated alongside pro international skateboarders who sought out the church as a destination. A free yoga class met on occasion. Rappers, metal bands and dubstep D.J.s all performed there. A crew of queer quad skaters came religiously. Local parents brought their toddlers to ride around on tricycles. One roller skater preferred the comfort of a dinosaur costume. Nuns who had been part of the church before it was abandoned by the archdiocese in 1992 would visit, thrilled to see the church playing an active role in the community again. It was a place where people could feel safe and be free.

The goal had been to save the church, but now it was gone, and we’d failed. Our years of relentless optimism had turned to rubble. It was crushing. The fact that it ever existed at all was a miracle. Proof that transformation is possible anywhere. Even in the land of vacant lots, Dollar Tree stores, dusty red brick buildings and payday loan signs.

A community isn’t a building, and St. Louis is shockingly resilient. In the days that followed the fire, we held emergency community meetings. Over 200 volunteers showed up to secure the building and clean up the mess the fire left behind in the neighborhood. A group of grade schoolers raised money to pay for supplies with a lemonade stand. We are planning on rebuilding. After all, who but us is interested in making our particular patch of unwanted earth more beautiful?

Seeking the thrill: Extreme hikers go the distance

They had been in Nepal for a week trying to reach Thorong La Pass, 17,769 feet above sea level, when they were caught in a snowstorm, unable to make it to the nearest village.

Avalanches roared down the mountain.

Jeremy Aerts and his girlfriend May Wong pressed on: Extreme hiking enthusiasts, they had committed to making it all the way through.

For some people, the idea of facing such obstacles – especially voluntarily – seems crazy. And yet many in the extreme hiking community wouldn’t have it any other way.

The new film “Wild,” based on the memoir by Cheryl Strayed, chronicles a grueling solo hike along 1,100 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail, on the border with Mexico, after Strayed’s divorce and the death of her mother.

The movie, which hits theaters Friday, might encourage more travelers to try extreme hiking.

Aerts, 30, a GIS analyst from Pittsburgh, describes that night in Nepal this past spring as the closest he has ever been to death.

Despite being unable to see 10 feet ahead of them, Aerts and Wong continued.

“At one point the wind was so strong it knocked me off my feet,” said Aerts. “We had to break into an abandoned cabin just before dark to spend the night with our guide and another trekking group.”

The payoff came the next day when the couple reached the tiny village of Muktinath, surrounded by Himalayan peaks.

“It was one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever had the chance to see,” he said.

And that, in a nutshell, is why Aerts hikes.

“I love the sense of adventure and challenge that it presents,” he said. “I like the idea of never really knowing what to expect around the next corner.”

Mohit Samant, a 27-year-old software engineer from Kansas City, Kansas, got a similar feeling about hiking when he visited Guatemala a year ago in his most memorable of many hikes.

He had half a mind to quit midway through his hike through the Pacaya volcano due to the incredibly steep terrain, but the hikers with him motivated him to continue to the top.

Ultimately, he said it was the best hiking excursion he has done.

He was able to admire views of three other nearby volcanoes: Agua, Fuego and Acatenango, making the whole experience – three hours on foot – well worth it.

Besides the surge of adrenaline, these adventures pay off with some amazing photo ops. Check out the gallery to see more photos you can only take on extreme hikes.

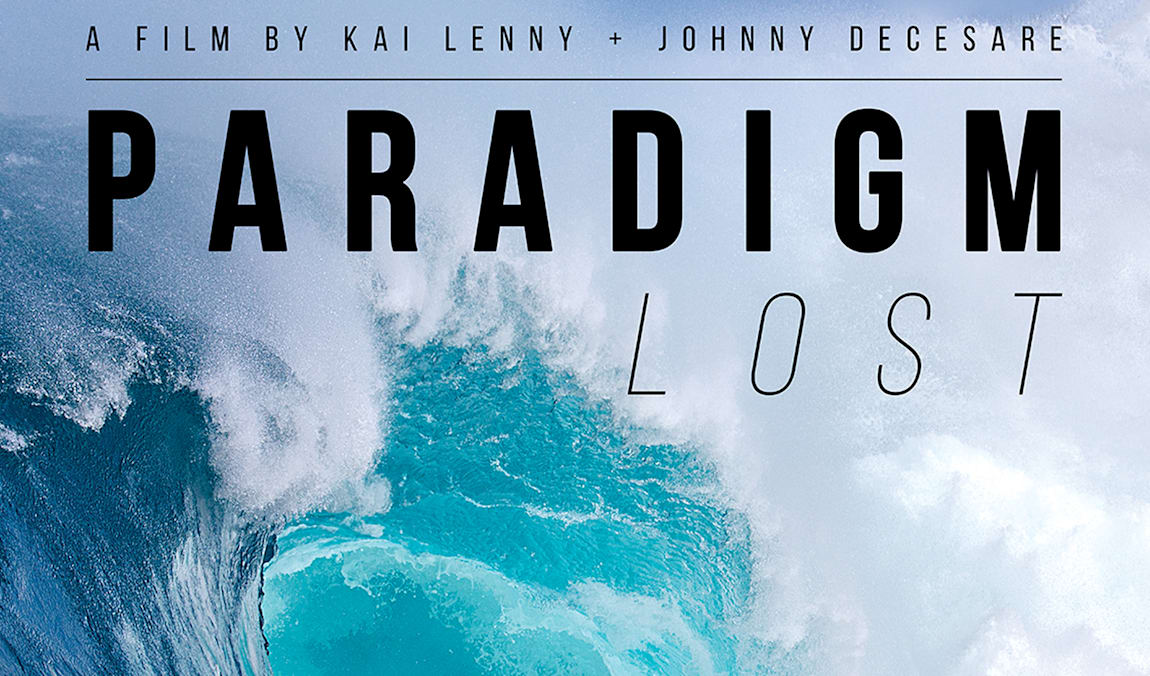

adventure surfing movies

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their bliss.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their work.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their videos.

The Adventure Film Festival is all about helping those that adventure to profit from their expertise.

The Adventure Film Festival is a global online adventure film competition.

IF you have an adventure film worthy of global recognition = submit it.

IF you are an adventure film maker = build your story / build your brand; it is our job to help you build your business.

Adventure Film makers / our stars – we want to help you develop our global industry…

WE hope you enjoy the news / videos / ALL that we do for you…

This is your 1-stop home cinema for the best surf movies playing online

Summary

-

1The Source

-

2For The Dream

-

3The Seawolf

-

4Skimboard Nazaré

-

5à la folie

-

6Beyond the Lines

-

7Shaping Jordy

-

8Shaka

-

9OUTDEH

-

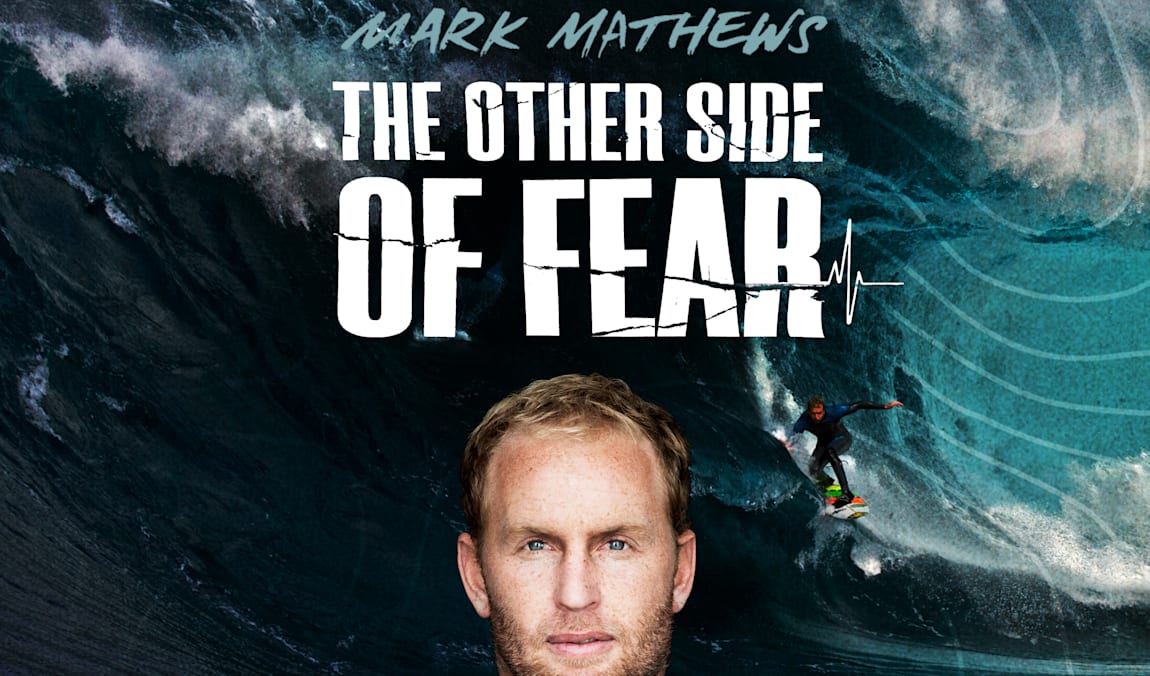

10The Other Side Of Fear

-

11Riss

-

12And Two If By The Sea

-

13Coldwater Journal

-

14Fish

-

15Under An Arctic Sky

-

16South To Sian

-

17Generations: The Movie

-

18Paradigm Lost

-

19Chasing the Shot

-

20Let’s Be Frank

-

21Strange Rumblings in Shangri La

-

22One Shot

-

23Exploring Madagascar

The Source

33 min

The Source

Koa Smith goes on a South African surf adventure, where waves (or lack thereof) lead to profound discoveries.

For The Dream

1 h 35 min

For the Dream

Ex-pro surfer Ben Gravy sets out on his dream to become the first person to surf in all 50 US states.

The Seawolf

43 min

The Seawolf

Award-winning filmmaker Ben Gulliver follows seven surfers on a two-year journey in remote, freezing waters.

Skimboard Nazaré

28 min

Skimboard Nazaré

Brazilian skimboard world champion Lucas Fink faces Portugal’s iconic Nazaré wave with a skimboard shape.

à la folie

33 min

à la folie

Strap in for the ride of your life as we follow Justine Dupont through a ground-breaking big wave season.

Beyond the Lines

43 min

Chapters

Travel with surf star Kanoa Igarashi for insider access to the World Championship Tour.

Shaping Jordy

48 min

Shaping Jordy

Ride along with Jordy Smith and Mikey February as they cruise the South African coast in search of waves.

Shaka

1 h 17 min

Shaka

Mathieu Crépel shifts his focus to the ocean and takes on one of the world’s biggest waves – Jaws.

OUTDEH

1 h 18 min

OUTDEH

Three young Jamaican men share their stories: a rapper, a surfer and a resident of Tivoli Gardens.

The Other Side Of Fear

58 min

The Other Side of Fear

The inspirational tale of big wave surfer and keynote speaker Mark Mathews and his journey back from disaster.

Riss

41 min

RISS

From director Peter Hamblin, follow surfer Carissa Moore around the 2019 World Surf League Championship Tour.

And Two If By The Sea

1 h 43 min

And Two If By Sea

Watch the iconic story of sibling rivalry between pro surfers and identical twins CJ and Damien Hobgood.

Coldwater Journal

43 min

Coldwater Journal

Follow surfer and filmmaker Ben Weiland on his decade-long journey to explore the world’s coastlines.

Fish

1 h 22 min

Fish

Discover the origins of fish surfboards and meet some of the pioneers who changed surfing culture forever.

Under An Arctic Sky

40 min

Under an Arctic Sky

A group of surfers, along with photographer Chris Burkard, journey to Iceland in search of perfect waves.

South To Sian

2 min

South to Sian

What began as a three-month surf trip off the beaten track turned into a two-year odyssey of exploration.

Generations: The Movie

38 min

Generations: The Movie

Join generations of pro surfers as they give an ode to the old days while looking to the future.

Paradigm Lost

1 h

Paradigm Lost

Featuring Waterman Kai Lenny

Chasing the Shot

23 min

Chasing The Shot – Leroy Bellet

Come join Leroy Bellet on the hunt for the photo of a lifetime, from his home waters on Australia’s South Coast to the notorious Teahupo’o in Tahiti

Let’s Be Frank

50 min

Let’s Be Frank

Who is Frank Solomon? A man? A myth? The two might just be inseparable.

Strange Rumblings in Shangri La

52 min

Strange Rumblings in Shangri La

A Worldwide Surf Expedition

One Shot

Exploring Madagascar

26 min

Exploring Madagascar

Slade Prestwich, Frank Solomon and Grant ‘Twiggy’ Baker embark on an epic surf adventure to Madagascar.

My Paragliding Experience in Cape Town

Hi everyone! Today, I’m excited to share my paragliding experience when I was in Cape Town last year (2014). This post is LONG overdue, given that I had been meaning to write it before I got engaged, married and all!

What is Paragliding?

Paragliding is an adventure sport where a person glides through the air using a wide canopy, a fabric wing that’s made up of a large number of interconnected cells. In paragliding, the pilot “takes off” from an elevated position, usually the top of a hill or mountain, then uses wind forces to help him maintain flight — sometimes even gaining altitudes! Throughout the flight, the pilot sits in a harness suspended below the wing.

While skydiving only lasts for a few minutes since you’re free-falling (and slowing your descent with a parachute towards the end), a skilled paraglider — relying solely on wind forces and thermals — can stay in flight for HOURS and cover hundreds of kilometers!

Spontaneous Cape Town Visit

So last year, I was in South Africa for personal travel. PE Reader Lizette learned about my South Africa trip on Facebook and graciously offered to host me if I were to visit Cape Town. So excited to receive her invitation that I took it up right away!

I subsequently learned that Lizette is a licensed paraglider and she has licensed tandem-paraglider friends who could take me paragliding if I wanted to. Since I had never done any extreme sport before, I immediately said, “YES!!!”

Paragliding at Lion’s Head

In Cape Town, there are two popular paragliding launch spots: Signal Hill and Lion’s Head, which are 350 meters and 669 meters above sea level respectively. Lion’s Head is the more popular spot, since it allows for a longer flight and better flight scenery.

I’m lucky enough to have paraglided from Lion’s Head, not once but TWICE during my trip!

At the entrance of Lion’s Head

At the foot of the mountain

They say that if you want something, you need to earn it. Well, that’s true in this case — before you can launch from the mountain top, you need to climb up the mountain first… and FAST, because you need to catch the wind conditions while it’s favorable for flying!

Lizette and Ian, getting ready to trek up Lion’s Head

End destination: the mountain top!! It looks near, but it really isn’t!

Mid-way through the trek, I was already huffing and panting, and I was only carrying a camera. I have NO idea how Ian managed the trek with his 20-odd-kilo backpack filled with tandem paragliding equipment — and he was scaling up the mountain faster than any of us!! I guess he’s used to it since he does this all the time?

Ian scaling the mountain like a ninja

While trekking, I could see paragliders launching off from the mountain top. That really got me excited (and nervous at the same time), as it hit me that I was going to be flying in a few minutes!

Paragliders launching off Lion’s Head (Cape Town)

Preparing for the Flight…

After about 15 minutes, we finally reached the launch spot!

Ian and team setting up the paragliding launch pad. You’re supposed to run from the top of the mat, DOWN the mountain, and “catch” the wind with your canopy, and then take off if everything goes well. It’s possible to trip, fall, and get seriously injured in the process. It’s also possible that you don’t take off at all and get caught in the bushes while running, which will leave you injured as well. (And this can be highly dangerous.)

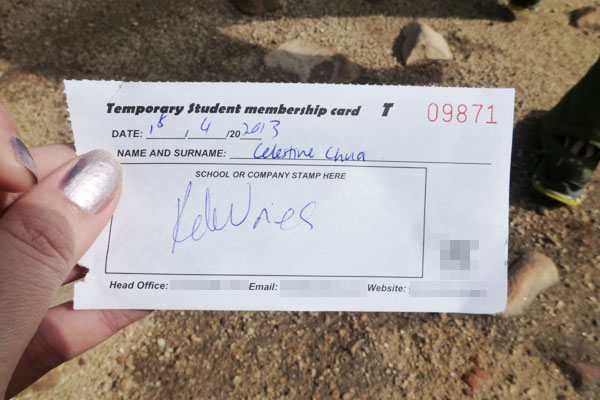

Since paragliding is an extreme sport filled with many risks (you can get injured or die), I had to sign an indemnity form before proceeding. It’s standard protocol and it’s to indemnify Ian of any issues that might arise from the flight.

Ian preparing the paragliding indemnity form

As Ian joked, “Here’s your flight boarding pass!” 😉 And I jokingly responded I got a one-way ticket! (You can only paraglide from top down, not bottom up!)

Ian meditating and praying before the flight… Actually I’m just joking, I think he was just assessing the wind condition to see if it was good for flying.

Me before gearing up. The wind is STRONG up here!!

All geared up and ready to fly!!! That’s Lizette preparing the launch mat up there!! (Thanks Lizette! 😀 )

View from the launch pad, before taking off

My Paragliding Flight

Now as for the flight itself, it’s best to show it to you in video-form. I’ve uploaded a video to YouTube comprising of my takeoff, flight highlights, as well as the *a-hem* landing. 🙂

Are you ready? Well, buckle your seat belt, and then click “Play” on the video below! Let’s get flying!! 😀

Snapshots from the Flight

Here are some shots from my flight!! 🙂

Magnificent view of Cape Town from the sky

Check out the beautiful blue skies and sea in the background!

Look at me pilot the paraglider!! 😀 (And Ian’s screaming, “Save me!!!”)

In case you are wondering why I was wearing purple leggings in the previous picture but jeans in this one, that’s because I changed my pants while in the air. 😀 … Just kidding, they are simply photos from two different flights!

Cape Town beneath our feet!!!

Ian and I before the flight

A glorious shot of us after the flight. That’s Lion’s Head in the background!

My Thoughts of My Paragliding Experience

If you’ve watched my video above, my reactions and emotions during the flight say it all. 🙂 Throughout the flight, I was feeling pure joy and ecstasy. It was incredible looking down from my seat, seeing myself float above Earth (with Ian behind me), suspended by nothing but a canopy and a harness.

In the meantime, everyone below — cars, people, restaurant waiters, fellow paragliders, etc. — was going about their own routine, without a care in the world, without even knowing that I was up there flying and having the time of my life.

Being up in the air, flying in the glider, made me feel tiny. It made the world feel tiny, given that everything (and everyone) was just beneath my feet. It also made my problems, concerns, and thoughts seem tiny. Up there in the sky, nothing matters. All you experience is purity and serenity.

I can understand why people like Ian and Lizette would fall in love with paragliding, and I’m thankful to tandem-pilots like Ian for showing this aspect of the world to non-paragliders like me. Without them, I would never have gotten to fly at all. So, a huge thank you to Ian and Lizette for making this possible for me!

I personally think that extreme sports like paragliding or skydiving is something that all of you should try at least once in their lifetime. It’ll tingle your worldview and your senses after you do it. After all, when you’ve just spent the last few minutes of your life suspended hundreds of meters above ground and seeing the world pass you by, you can’t help but have some perspective shift in terms of how you see things, even if unconsciously.

Of course, take all safety precautions and only fly with licensed tandem pilots, and not people looking to make quick bucks. There are licensed pilots charging people for tandem flights who are not licensed tandem pilots — and having a pilot license is totally different from a tandem pilot license. Make sure to always verify and ask for tandem-pilot certifications before registering for any extreme-sport activity — not taking proper safety precautions can result in serious injury or even death!

Ticking Off Item #113 of My Bucket List

By way of my paragliding flight, I got to tick off an item off my bucket list, which is “to fly” (and I don’t mean flying by plane).

Do you have your bucket list? If not, maybe it’s time to create yours! 🙂 Read my bucket list article 101 Things To Do Before You Die.

By Celes, Personal Experience

For more information and details : https://personalexcellence.co/blog/paragliding/

Trails for Everybody

An interview with Gabo Benoit, trail advocate and mountain-bike mayor of Coyhaique, Chile.

Despite the pandemic, Gabo Benoit hasn’t stopped advocating for trails around his home in Coyhaique, Chile. Writer Teal Stetson-Lee caught up with Gabo via Zoom, to hear more about his recreation-based conservation efforts and the evolution of mountain biking in the Aysén region.

I first met Gabo in February of 2019 at his home in Coyhaique, where he was cheering on his daughters, 7-year-old Amalia and 5-year-old Maite, as they fearlessly rode their bikes off tiny wooden jumps in the backyard. It was a fitting intro, and the whole family immediately welcomed us.

As it turns out, Gabo also has a history in professional mountain biking as a national champion downhill racer and Enduro World Series competitor. His racing experiences reflected his unconventional approach to life and served as a catalyst into his current roles as a mountain-bike guide and Patagonia brand ambassador in Latin America. Gabo’s dreams and goals have always been bigger than bike racing, having dedicated himself to strengthening his community and homeland against economic hardship and environmental destruction.

Gabo and I share a deep interest in the convergence of outdoor recreation, conservation and community, and we’re glad you’re all joining us as we continue that conversation. Welcome.

Teal Stetson-Lee: Hello, Gabo! It’s great to see you. Where are you right now? And what are you up to?

Gabo Benoit: Well, well. Hello, Teal. Nice to see you too. I’m here in the store. The store is now closed for two hours. I’m in Coyhaique. It’s a beautiful day outside. I’m great.

TSL: Wonderful! So, give me a little bit of background on yourself in a few sentences.

GB: A little bit background, like little words for me? Adventure! I don’t know what else. My life is an adventure. My whole life has been like that, taking things in one minute and trying to make it out and always focusing on what I love in my life: wheels, nature and conservation. I think they’re so important, those things for me.

I started coming down here to Coyhaique and Patagonia [the region] when I was really little. I was like 8 years old, and I was involved in fly fishing. An uncle of mine told me how to fly fish, and that was a real connection with nature and everything. I think my uncle was not so happy because this little kid was here every summer, trying to go fishing.

From 4 years old, I was involved with two wheels. I started racing dirt bikes, motocross. My father is a fanatic about rally cars and everything with wheels. Bikes and mountain bikes were in me since I was 4, but the connection with nature and trying to see how important it was to save our environment and our animals, that happened around fly fishing for sure. When I made my first catch and release, I understood we must have respect.

TSL: Wow, that’s amazing, to be introduced to that at a young age. Well, speaking of a young age, how are your daughters now? Are they still riding off mountain-bike jumps, and how big are those jumps now?

GB: No, now we have a big pump track here in the lodge, and we have a course with little stairs and jumps and everything. They train like two days a week here with the teachers that we have in the school. They’re growing a lot, a lot. They are still good riders. They’re awesome. And we have Gabito, who’s one year and a half.

TSL: He is your new son?

GB: Yeah! He’s using the push bike now.

TSL: I guess they’re taking after their Papa.

GB: Yeah, yeah. I guess so!

TSL: And you had a successful career as a professional mountain biker. How did you get into mountain biking?

GB: Well, I got into mountain biking when I was little, but not racing too much. I used to race a lot of dirt bikes, and I was pretty good. I got in an accident when I was 16 and broke two vertebrate, so I stopped racing dirt bikes, and I say to my mom, “OK, Mom. I’m gonna sell my motorcycles and buy a downhill bike.”

I didn’t race for too many years; I think five years in total between junior category and elite. I like to push a lot. When I do something, I want to do it good. That’s the way for me. I want to be professional in what I do.

It was hard because in Chile, families tend to be super traditional. So, this 18-year-old guy who want to be a professional mountain biker and fly-fishing guide—this was rare. But my mother always supported me. I told her, “Mom, I don’t wanna study. I wanna be a professional.”

“You want to be a professional?” she said. “OK, I’m going to support you. I will not give you money to race, but you must be the best. If you want to go training, I will take you there, but you must be the best.”

I was racing half the year, and the other half I was fly-fish guiding down here in Patagonia.

A big part of my family did not agree with this. But of course, sports give me a lot of things, taught me that nothing was impossible. Sport showed me how to set steps and go over those steps. That was something very important in my life.

TSL: That drive from your sports culture and mountain biking has translated into where you are now with all your ambitions?

GB: Yes. I retired in 2002, as the number one in Chile, but maybe if I hadn’t, I could be in the World Cup. But I was very realistic about that; it was super hard to live on mountain biking in Chile. There was no support, there was nothing.

But I have other things here like guiding, fly fishing, that gave me that connection with nature and that I could live on. And after I retired from mountain biking, I didn’t ride for maybe 10 years.

Then one day, after I was married to Carmen, I said, “OK, I want to stop fly-fish guiding a little bit, and I want to start mountain biking again.” And I saw that where I live in Coyhaique, there was a lot of opportunities to create something with mountain bikes. I had all this experience taking care of the fly-fishing clients, so I used that experience and started to make mountain-bike groups and develop some trails. And that started working. When I first started, everybody looked at me and said, “What are you doing? You have been guiding for 15 years, and now you’re gonna guide mountain biking? There’s nothing here. Are you crazy?”

“Yeah, I’m crazy, but I believe in this.” And now our business is 100 percent about mountain biking. The lodge is focused on mountain biking. We have the bike shop. We have the mountain-bike school. We support the trail-building crews. I realized one thing that I really, really love is mountain biking. And now, I have more support than when I was racing. It’s my passion. Now, I live for mountain biking.

TSL: That’s neat to hear about that evolution in your career and part of that support has been the Patagonia brand. How did that relationship come about?

GB: That relationship started about eight years ago when I was fly fishing. We made a video down south here, with my dog and a really crazy crew of friends. We went exploring where nobody goes, and a big relationship started. Patagonia is a great brand, and it’s so cool that they are not interested in the World Championship but rather people who take care of what we have around us. For me, Patagonia [the brand] has been crucial. It’s awesome. I’m not in the good shape, but I love mountain biking, so they support me. That’s where you understand that they’re thinking about other things. We want to save our planet.

Where I live, I see that there are not too many opportunities for a lot of kids to go and study outside, but I saw the opportunities I have here without being a local. There’s a whole new crew of kids that are mountain biking now. Of course, they wanna be racers, but I tell them, “Hey, man, you could live for this, but it’s not all racing, so racing is not everything. This is a lifestyle, and if you love mountain biking, there’s a lot of ways to live on it. There are so many things beyond racing. It’s awesome, but there’s a lot of sacrifice behind that—a lot.”

TSL: I love that, Gabo. I can relate to that, that dream of being a professional athlete that kids have. And you’re sharing with them new ideas about what you could do with mountain biking and how you could diversify and still hold that as the passion that is your compass for what you’re doing with your life.

That actually gets me into the next question I have for you, about mountain biking in Chile. How would you describe the culture of mountain biking in Chile right now?

GB: I think it’s expanding a lot. It’s becoming a lifestyle. Of course, there’s a lot of racing, but if you go to a mountain-bike race, when it’s over, everybody is with their families, everybody is enjoying together. I think it’s a different way of racing, a mix of racing and lifestyle.

I can see in our business that mountain biking is becoming a lifestyle. A lot of groups, they don’t race, but they have all the same T-shirts, their groups have a name, and they go out together every weekend or three times a week. That’s culture.

We have an amazing, amazing country. We have a lot of mountains, a lot of mountains, and where I live, in Aysén, mountain-bike culture is new. Not more than 10 years.

TSL: Tell me more about where you live, for those who are listening. Tell us about the Aysén region. What is it like?

GB: First, the Aysén region is one of the largest regions in Chile. We have everything. We have from the sea to the border with Argentina, where it’s super dry. We have rain forest. We have ice fields. We have a lot, a lot, a lot of lakes. We have everything in one region. It’s awesome. It’s beautiful.

We are a ways from Santiago—about 1,000 miles [1,600 kilometers] south of Santiago. You could get here on a straight flight that is about two-and-a-half hours. As a region, it’s super new. The city of Coyhaique is maybe 100 years old. It’s hard here, very windy and cold. Living here was not easy in those early years. But Coyhaique has everything. You go east and you have the flat land, which is drier. You go west and you’ve got the rain forest. Mountains are great. We have big forest. The dirt is awesome. We have grip all year.

TSL: I have been fortunate enough to see a little bit of your amazing region, and I love hearing you describe it. I am curious about a lot of the trails you’re building and riding. They’re old resource-extraction roads, maybe even generational Indigenous pathways, and I want to know, how do trails fit into the culture and history of the Aysén region?

GB: Well first, the main activity in the Aysén region for a lot of years, and one of the main activities now, are cows or other farm animals. So, there are a lot of trails. And the locals, when they raise cattle and have to move them to Coyhaique, sometimes it’d take three months getting all those animals to the place where they sell them. All those trails are there in the mountains. Today, they bring a truck and put all the cows in the truck.

We have been making the long process of scouting all—not all, but part—of those trails and trying to clean them up and use them. They have a big history.

Another thing that we have been doing. There was a lot of wood extraction in the mountains, so a lot of places have lots and lots of fire roads, and we have been working on making trails over those fire roads. We have a long ways to go; we’re just starting. I know that we have maybe 10, 20 years more, right? The next generation is going to have a lot of trail, but they’ll still have to work for them. But there are endless possibilities here to make good trail systems—not easily, but they might not have to build from zero.

There are a lot of people that live in the mountains now that take out firewood. In La Gloria (a large, privately owned forested area outside of Coyhaique historically used for firewood cutting), there is one guy who bought a little mountain bike because he sees us every day riding our bikes. So, he decides to buy a bike to carry his chainsaw for cutting. But that’s the first step. Now, he’s riding a mountain bike to go make firewood; maybe in two years, he’ll have more attention for the trails.

TSL: You’re inspiring locals to think about their own lifestyle and incorporate mountain bikes into what they’re doing.

GB: Yes, firewood here is important for a lot of people because they have made their living about that. But those people … they love the mountains. They live in the mountains, so if you could give them another way to conserve and to live in the mountains, I think that’s the key. That’s what I want to work for, how to give value to that. How to show them that maybe instead of cutting the trees, let’s take care the trees. That’s our vision.

TSL: I know one of your passions is growing outdoor recreation as an economic force in your area, maybe into something people will want to do more than collecting firewood or some of the other extractive industries in your area. Tell me, what has motivated that push from you to try to increase outdoor recreation?

GB: Well, first, I want to say we always use our mountain-bike tours to open these places. A lot of the local people may not agree with us because we’re paying the owners of these farms for access. Most of these places, they aren’t open to everybody. The local people don’t understand that my vision is like, OK, let’s go in with the tours first. Let’s show them the mountain bikers can conserve, that they can live with mountain biking and mountain bikers are not so bad. Then the owners agree with us and say, “OK, let’s open it now. Let’s be part of the trail system for the community.”

We are always thinking about opening these places in the future to everyone, but you have to understand that you’re going on a mountain bike into a place where people have never see a mountain bike. So, we don’t want to go in as an invasion; we want to go little by little, and then that man you saw cutting firewood is now riding a mountain bike, and the owner of that big farm now wants to build more trails. Then we’re ready to open it. Because we know that we could handle that.

Sometimes what happens here in Coyhaique is that owners of farm give a space to make some trails, but nobody take cares of them. Most of the places we use, I pay for the access and build the trails—so, I was pretty much paying to use my own trails. And people ask me, “Hey, but how is that your business?”

Well, I know that this is not a business, of course. But I have to do it. This is the way to show the owners that we can make something, because we have to start conservation in all these big private farms that are getting exploited. We have to change those owners, show them how to do conservation. Sometimes to a farmer, conservation sounds like, “Whoa, no, no, no, no. I don’t want that for my farm.” But we can make conservation about sports. We can use other kinds of conservation.

I agree that there are some places where, if there hasn’t been a trail, there doesn’t need to be. I’m not gonna go build a trail in the national park, of course. No, we need those spaces for animals and everything. But we do have a lot of private lands, and those private owners want to make trails. We have to show them that we can be respectful, that we are not going to light their farms on fire, that we respect the other things that they are making inside those farms.

For me, that can be really hard. Sometimes, we build a trail and by afternoon there are 10 cows walking up our trails, so all the work of the day is gone. It’s like, “OK, tomorrow I’m gonna make it again, but please, could you take care about the cows, man?” But that’s part of making this grow.

TSL: What motivates you to do that, Gabo? That sounds like a lot of work to convince farmers and ranchers and private landholders to get on board with your vision. How are you motivated to do that?

GB: One thing that was really cool, in La Gloria, most of the people that live there didn’t know about the highest part of the farm—it’s like the top of the mountain. When they saw us riding bikes up there, I say, “Yeah, I build a trail to the top.” “What?!” “Yes! I’m going to show you the top of your mountain. You have never been there?!”

When we open these kinds of spaces, the owners are happy. They know their place now, what they have and what they could do. When they’re walking a beautiful trail on their land, they are like, “Wow, this is beautiful.” “Yeah, this didn’t exist. We made it.” They start to see the potential that they have, and they can imagine the future with this.

We got one project I have been pushing for like five, six years, that is La Gloria. The owner is a great, great, great man called the “Capitán.” Of course, Capitán works his farm with all this crew that cuts the woods, but he gave us the opportunity to make these trails and to start developing this farm. It’s super big, and it’s close to a little town called Villa Ortega, a super little town. Now, we’re figuring out how we connect this town with all these places we want to protect. But we don’t want to go there and say, “We’re gonna do all this conservation and you can’t cut any more firewood here.” No, no, no, no. Let’s see how we could all share together because I know that in another 10 years, we’re gonna have more people maintaining trails than taking out woods.

If you don’t try it, you never know. Sometimes you win, sometimes you don’t.

TSL: Spoken like a true visionary. In parts of the US—including where I live right now in Rico, Colorado—outdoor recreation has become so popular that it’s become its own sort of extractive industry, where crowds damaging sensitive habitats and overwhelming local communities is a common trend we’re seeing. Do you fear outdoor recreation could become something similar for communities and environments in the Aysén region, and if so, in what ways do you think it could be managed?

GB: One hundred percent. I think outdoor recreation could be a big thing, big, big because we have everything. And I think the way to do that is working in these little towns and with kids. We’re losing localism. Kids, when they turn 15, 18-years-old, most don’t have the opportunity to go study. But nobody has shown them all the other things they have around. They have the mountains. I didn’t study anything. I live on this, and I am not a local. I don’t have a history here. They have everything, but we need to figure out how we give them the tools to realize that there is an opportunity because I know that not every one of those kids want to work on the farm.

And I’m not saying about that they’re going to lose their gaucho [South American term for “cowboy”] culture. No. They’re still gonna be gauchos, but in a different way. They’re never going to lose that culture. But if they don’t want to build fences, maybe they could hop over a mountain bike and guide or over a horse or walking or hiking or fly fishing. Why not? Why not? We need that. Give them the opportunity to know the sport, maybe know another language. But they have everything else. They have history. They are gauchos, and they’re gonna be gauchos over a mountain bike or over a snowboard.

I think that’s how we make that localism stay here and not go outside the region. Because it’s super easy for them go work on a fish farm or going to the mines. That’s the easier way. Or they come down to the city and we’ve lost them. We’ve lost a lot. It’s hard, but we need the spaces for them to do that.

I know that a trail system is more than having fun over the bike. That’s my view. I love to ride good trails, but I know that a trail is more than fun.

TSL: So, you are saying that the generations to come could manage these trails? And that staying there and having the passion for building those trails, or being guides in the area, and loving their place and the lands that they come from is going to help create education for everybody? And right now, you’re just trying to get your feet underneath you with trail networks in general, because there’s not much. Is that right?

GB: Yes, and that’s it. I think that’s what we need. I started realizing that, when I was a fishing guide, I looked around and thought, “There isn’t a new generation of guides. What are we doing wrong?”

We start doing this with all our businesses, in the tour company, then the store, then little things that help us bring all these together and try to support the trail builders. Now, we are trying to build a foundation working with these local communities. And more than focusing on Coyhaique city, I want to focus in little communities. That is where we have to go. I don’t want to say that in Coyhaique there’s no culture. Yeah, there’s a lot of culture. But it’s a big city. You have more opportunities.

In those little towns … that’s where you live in the real Patagonia.

TSL: That’s a lot of hard work, Gabo. I’m sure this past year has been a little bit crazy for you, as it has been for most of us. COVID-19 has disrupted life around the world, and we even had a delay in this interview because of the COVID-19 surge in Coyhaique. Can you tell me how the Aysén region is doing now?

GB: Well, this region receives a lot of tourists. So, all this season has been really, really hard. We didn’t receive any bike trips since March of last year. We’ve been through one year without working. But I’m happy that we just have the store, the bike shop. When we started the bike shop, we had nothing. I said, “OK, how are we gonna make it?”

The bike shop is doing really well now. We don’t have too many bikes, but we’re selling bikes, and it gives us a little bit to continue supporting all our team and that was super important for us.

We know that this is gonna end. I don’t know when, but I hope the next season is gonna be more like normal. A lot of people want to come, that’s true, and you could see that. We have to wait, be patient. There’s no option, just be patient.

Sometimes, I said, “OK, maybe I should stop.” No, I could not stop, I could not stop. This is for new generations, and one day all my trails are gonna be open for everyone. But somebody has to do it, and you cannot go to a place that’s not yours and open a trail for everyone and then make a mess. That doesn’t work. And this is so new here, that’s why. So, we have to take care about that.

I can see that because like 20 years ago, when we were starting into fly-fishing guiding, you could go everywhere. But then some guys start jumping inside the gates without permission, and some places were closed. Then that great lake when you go fishing, now you cannot get in. So, we have to make things right.

I know that all the trails I have been working on and paying for, I will never get that money back. I know that. But I’m so happy when I see that they can make a living doing that, and if we could give that little piece of help—that’s for all of us.

TSL: I admire that so much about you, Gabo. In seeing the potential for being able to create more sustainable jobs in trail building. And having trail building be valued because it’s ultimately a way for people to get into the outdoors and learn about nature and learn about the places that they live. And I hear you say how challenging it is and luckily you have that professional mountain biker in you, that won’t give up. And this has been a wonderful conversation. Is there anything more that you’d like to add?

GB: I just do this because I love it. It’s not for ego. It’s not because I wanna be recognized. No, this is for everybody. I want to make something for the region. It doesn’t matter if my name is there or not. I love this. It’s my passion, it’s my life, it’s my lifestyle. And I hope I can push for that a lot of years more and try to change people minds to see that there are other opportunities. We live in an awesome place, and all Chile—it’s great.

It’s great to see how you motivate some people. For me, it’s so important to have Edecio and and Juan and the other trail builders. And maybe we are a little community here now, but we are real community. We are living doing what we really love, and that is mountain biking.

And this is for everybody. Trails for everyone, that’s it.

By Teal Stetson-Lee, Patagonia.com

For more information and details : https://www.patagonia.com/stories/trails-for-everybody/story-100702.html

Extreme adventure at the edge of the word: sail and ski in Norway

There are few more thrilling places to ski tour than the Lyngen Alps, a 55-mile chain of peaks that punctuates Norway’s fragmented northerly fringes.

“Sometimes you have to do things you’ve never done to get to places you’ve never been.” These are the words of wisdom offered by our mountain guide, Espen Minde, as we take a break from climbing 1,000 metres on skis up an unnamed peak in Norway’s Lyngen Alps. Something, indeed, I’d never done before. We’re also climbing straight into a blizzard. Normally, in conditions like these, I’d have turned back or maybe not even set off in the first place. But Espen, being a Norwegian mountain guide, isn’t put off by driving snow, howling winds and zero visibility. And as our group — comprising six other skiers — has every confidence in Espen’s years of experience touring these wild, often unnamed mountains, we plough on.

Ski touring in the Lyngen Alps isn’t always like this, of course. Aboard the Arctic Eagle catamaran, the comfy floating accommodation for our ski and sail trip around Norway’s northeastern shores, we’ve seen all weathers. On the first day, having sailed for three hours from its base in Tromsø, Arctic Eagle anchored off the coast of Vanna island, afternoon sunlight glinting on the waters of the fjord as our captain, Håkon, ferried us to the rocky shoreline.

Once on dry land, we start our 1,031-metre ascent of Mount Vanntinden. The snowbound peaks of the Lyngen Alps bear down on us from all quarters, rising majestically up into a baby-blue sky. There’s not a soul to be seen and not a sound to be heard other than the gentle lapping of sea against shore.

Espen leads us at a gentle pace, with breaks to take in the view. It’s late April and we’re well north of the Arctic Circle so we have plenty of daylight. The views as we ascend become more spellbinding, the slowly sinking sun casting an increasingly golden glow across mountains and sea. By the time we reach the summit, the sun is just above the horizon and we’re on top of the world in every sense. It’s high fives all round, a fast round of photos, then we need to get moving to get back to the boat before dark.

We remove the climbing skins from the base of our skis (the sheathes that allow you to ascend without constantly slipping backwards), flip our ski touring bindings to ‘descend’ mode, don a couple of warm layers, tighten up rucksack straps, clip into our skis again and set off downhill.

We’re able to spread out and enjoy big, swooping turns across huge snowfields almost all the way back down to the fjord, skiing into the setting sun, a glorious landscape of deserted mountains and dark-blue sea spread before us. Whoops and hollers of excitement are inevitable and why not? There’s no one else around.

Back aboard Arctic Eagle, everyone is ready for a beer, but not before one unavoidable Arctic ritual: a quick dip in the icy Norwegian Sea. With the water temperature at around 5C, no one stays in for long. Warm and buzzing after a hot shower, we gather in the catamaran’s galley around the large table to enjoy freshly caught cod and cold beers, before Captain Håkon, who’s sailing us east to anchor off the coast of Arnøya island for the night, shouts: “Quick! Come up on deck!”

The Northern Lights are doing their thing in the starlit skies above. A relatively muted display of pale-green swirling waves passing over us, but it’s a winning finale to the perfect day. Not every day is so blessed, of course. This is Arctic Norway and the only predictable thing about the weather is its unpredictability, but over the course of the trip we get to ski amid the most incredible scenery, in everything from sunshine to mist, sleet and snow. Eventually, six days after setting sail from Tromsø, Arctic Eagle returns us to its home port. Exhausted, sunburnt, weather battered and happy, we step ashore and say a sad farewell to Captain Håkon and Espen, safe in the knowledge that it’s absolutely worth doing things you’ve never done to get to places you’ve never been.

By Alf Anderson, National Geographic

For more information and details : https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/extreme-adventure-sail-ski-in-norway

A Breathtaking Mountain Trekking Adventure – A little Joy of life.

It’s not an adventure of a lifetime, because I have embarked on a journey to traversing a million paths and embracing a billion adventures. For I have begun walking on my soul-searching path.

I have heard people say that mountain trekking is a thrilling and awe-inspiring activity that allows adventurers to immerse themselves in the beauty and grandeur of nature. But from the moment I set foot on the rugged trails, I knew I was about to embark on a life-changing journey, and no words could surmise that moment.

This is not just a story of my unforgettable mountain trekking experience, but of my spiritual inner journey where I pushed my limits, embraced my inner strength, and forged a deep connection with the majestic peaks. As I stood at the base of the mountain, gazing up at its towering summit and soaking in the grandeur, a mix of excitement and nervousness coursed through my veins. But even in that moment of fear of the unknown path, I did not trace my steps back to the camp, something in my heart whispered, ‘Let’s traverse this path, for the mountains will lead me to the solitude my soul seeks’.

With every step I put forth, the mountains I carried on my shoulders started withering away. Every cell in my body pulled up every ounce of resilience and determination to cross treacherous rocky paths and brave winds that froze my skin. But it was precisely in those tough moments that my inner strength held me through and whispered, “Keep going forward”.

And if there was ever a fleeting moment of my resilience wavering, I found my courage amongst the group of absolute strangers who became a wolf pack during the trek, washing away my self-doubts with words of encouragement. With every step forward, don’t know how just those pack of strangers supported me throughout and contributed to making it possible to complete the trek, have gradually become friends’ alike family.

For every mountaineer, mountain trekking is not just a physical feat; it is a spiritual and introspective journey that is unique to each one of them. No doubt, trekking through mountains offered a captivating experience that intertwines your spiritual connection with the divine. This journey became heavenly with rugged landscapes, majestic peaks, and serene valleys enchanting the soul. The whispering breeze, the flowing streams, and the rustling leaves speak a language of volumes of solitude, revealing the divinity inherent in every natural spectacle.

It was that moment of solitude that silenced the noise of everyday life and I plunged deep into self-reflection, touched my nodes of self-love, and whispered a little note of gratitude to the mountains. Nature has always taught me invaluable lessons about patience, perseverance, and gratitude. But today it has brought me much closer to the Almighty in the true spiritual sense.

Mountaineering is not about the destination, it is the journey along the path, the moments that we feel with every step. It reminds me to cherish the present moment, as the journey itself is as important as reaching the destination. In the solitude of the mountains, I dwelled in inner peace being one with nature. Atop the summit, there I felt a sense of achievement and was humbled by the vastness that stretched before me. It was in this moment and the mountains that lead me closer to the realm of the gods. And with every breath I took, I felt my inner being’s connection with nature and the divine presence became overwhelming.

I knew I cannot stay at the peak of the mountains forever, and I would have to trace my path back to the base. I spread my arms out and sent a big hug to the vastness and a few moments later, I closed my arms and embraced the experience that overwhelmed me with emotions that I cannot put down in words.

Returning from the mountains, the experience stays with you forever and ever, transforming your perception of the world. Trek becomes a sacred pilgrimage, a communion with nature and a higher power where I, personally always feel a deep connection with the Almighty that comes along the way – a connection that reminds you of the magnificence of creation and the vastness of the spiritual journey that lies ahead.!

My mountain trekking experience was an adventure of a lifetime, etching memories in my heart forever. It taught me to embrace challenges, appreciate the beauty of nature, and discover my inner strength. Through the ups and downs of the journey, I forged lifelong friendships and gained a renewed sense of purpose. Mountain trekking has the power to transform individuals, leaving them humbled by nature’s might and inspired to conquer new horizons. If you seek an experience that challenges your limits and nourishes your soul, I encourage you to embark on your own mountain trekking adventure. It has brought a sense of perspective, reminding me to be humble, appreciate the small joys, and embrace a mindset of gratitude. This experience instilled in me a sense of responsibility to protect and preserve the natural wonders that we are fortunate to witness.

I’m eager to hear mesmerizing tales of your mountain trekking adventures; please do share with me the breathtaking moments, the challenges overcome, and the triumphs atop those majestic peaks…!

By

For more information and details : https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/breathtaking-mountain-trekking-adventure-little-joy-nair-kapoor